by Ya Sezi Bo Oungan, edited by Katherine Bonnabel

During the period between the 17th and mid -19th centuries it has been said that in the Southern parts of America it was better to be Native American than African, better to be a noble savage, than a non-human.

On Mardi Gras in 1885, 50 to 60 Plains Indians marched in native dress on the streets of New Orleans. Later that year, it is believed the first Mardi Gras Indian gang was formed; the tribe was named “The Creole Wild West” and was most likely composed of members of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

The Mardi Gras Indian “tribes” are a cultural and social function. However, the Plains Native American attire and art style that decorates their elaborate costumes was more of a mask, a representation of deeper African roots beneath.

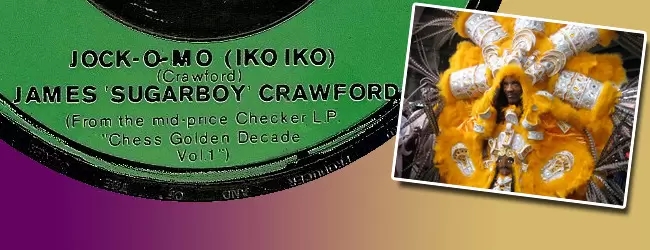

The famous and well-known Mardi Gras song “Iko Iko” depicts a scene between two bands of Mardi Gras Indians. Iko Iko was an Amerindian war call that was said like “Iko IKO!” and meant something like “Pay Attention”

The original title of the song “Iko Iko’ was “Jock-a-mo”. Chakamo was a greeting used in confrontation during battle meaning something like “It is good”, though also often cited as meaning Brother John or jester.

Mardi Gras Indians have several different positions within the tribe that play various traditional roles. Many blocks ahead of the Indians are plain clothed informants keeping an eye out for any danger. The procession begins with “spyboys,” dressed in light “running suits” that allow them the freedom to move quickly in case of emergency.

Next comes the “first flag,” an ornately dressed Indian carrying a token tribe flag. Closest to the “Big Chief” is the “Wildman” who usually carries a symbolic weapon. The Forward people like the Guidon or flag bearer, and the Back people like the Chief and the Wildman follow a very well-known Congolese style of the Mavile and Mavumbo, the warriors and scouts upfront and the chief and supporting priests and medicine people behind.

Mardi Gras Indians sing in call and response style songs. Mardi Gras Indian chants are believed to be influenced by various languages spoken in Louisiana through its history. Many of these words have no official spellings and are offshoots of multiple different languages, given the city’s long history as a port city. It is estimated that up to 50 African languages, German, English, English-based Creole and a French-based Creole all influenced the of language in New Orleans.

In many ways the Mardi Gras Indians are one of the only surviving examples of the “masquerade” style dances having social and community justice implications, like Abakua, a kind of costumed dance surviving in Cuba. (Also sometimes known as Ñañiguismo, it is an Afro-Cuban men’s initiatory fraternity or secret society, which originated from fraternal associations in the Cross River region of southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon)

Abakuá’s roots are found in the Ekpe Society, or Leopard society of Nigeria and Cameroon which confers high social status and political authority; these men participate in ceremonies concerned with ancestral spirits and are believed to protect the community through magic and religious ritual.

Around 1970-80 two stores would open up established by the same company, House of Marie Laveau and Rev. Zombie’s. These two stores would open, bringing Brazilian Candomble and Kimbanda statues to the tourist market, followed by the opening of F&F Botanica in ‘83. These stores would bring the Orisha to the people and thus how the Yoruba deities became a focal point in an otherwise Congolese influenced city.

Modern New Orleans Voodoo was also heavily influenced by the various Spiritualist churches including the Spiritual Baptists, that laid a foundation that modern and popular culture built upon.

Voodoo stands as one of the world’s most maligned and misunderstood religions. This is because of how voodoo is presented in media and pop culture. More accurate representations of Voodoo occur in connection with the popular culture of regions where Voodoo is actually practiced. Humanity’s relationship with spirits is the primary focus, and the care and healing of its community.